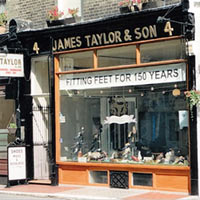

One of the real delights of having a pair of bespoke shoes made is the possibility of having exactly what one wants. Gone are all thoughts of having to 'make do'. Compromise can be banished. Sartorial perfection can be pursued with vigour. Style and workmanship must be considered carefully in these circumstances, of course. But there is another factor which can now also assume its proper importance: colour. For years I have had in my mind a particular colour combination. I first saw it in the footwear of an artist friend – a gentleman of exquisite sensibility, now, sadly, gone to his reward. I knew well enough that the objects of my desire would be impossible to find in the 'ready-made' world: only master craftsmen could create for me precisely the right shoes. This, then, was the reason for my visit to a modest, pleasingly old-fashioned shop, just off Marylebone High Street. Here I had found one of London's top makers of bespoke shoes: James Taylor & Son.

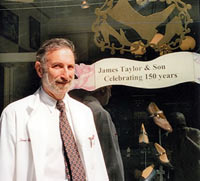

These premises, as you will note from my picture, do not shout their importance. Yet princes of the Church (like the late Cardinal Hume) and princes of finance (like the late Paul Getty), as well as princes of Europe's blood Royal, have been shod by James Taylor & Son. The firm moved to its current location in 1954, but James Taylor had walked to London from Norfolk to start his business nearly a hundred years earlier, in 1857. Now the Managing Director is Peter Schweiger (pictured), the fifth generation of his family to produce hand-made shoes. He is a quietly spoken gentleman, who trained as a forester before returning to the family concern. He was keen to stress that his absolute priority was to provide me with shoes which would be beautiful, comfortable (for the company has a special expertise in solving problems for those with 'difficult' feet) and made to conform to my wishes down to the smallest detail. I knew at once that Mr Schweiger was a good man.

These premises, as you will note from my picture, do not shout their importance. Yet princes of the Church (like the late Cardinal Hume) and princes of finance (like the late Paul Getty), as well as princes of Europe's blood Royal, have been shod by James Taylor & Son. The firm moved to its current location in 1954, but James Taylor had walked to London from Norfolk to start his business nearly a hundred years earlier, in 1857. Now the Managing Director is Peter Schweiger (pictured), the fifth generation of his family to produce hand-made shoes. He is a quietly spoken gentleman, who trained as a forester before returning to the family concern. He was keen to stress that his absolute priority was to provide me with shoes which would be beautiful, comfortable (for the company has a special expertise in solving problems for those with 'difficult' feet) and made to conform to my wishes down to the smallest detail. I knew at once that Mr Schweiger was a good man.

He shared with me some of the more unusual of his customers' requests. One fine fellow, for example, arrived from South Africa with the tanned skin of an ostrich he had shot himself and asked for shoes to be made from it – which they duly were.

My own requirements were less exotic. The colour combinations available to me were almost without number, but I knew what I wanted: black and grey. The effect should be almost as if I were wearing grey spats over black shoes - something I did, indeed, do in my daring youth. Mr Schweiger knew at once what I wanted, and produced a sample of dove-grey glacé kid leather of exactly the right tone. The style would be unusual, but quite possible: a whole cut galosh (that is, with no side seams), full brogue, Oxford cut, with a hint of chisel to the shape of the toes. The soles would be shaped in the manner of a violin, for greater lightness. As is my usual custom, I would have two rows of nails at the toe of each sole, to inhibit wear, and quarter metal heels, to make a pleasing 'click' on the pavement. The leather for the soles would be oak-bark tanned, from Barkers tannery in Devon, and the leather for the uppers would be from the Freudenberg tannery in Weinheim in Germany. Mr Schweiger wondered whether I might like the 'punching' on the toes to incorporate a monogram of my initials, but – displaying an uncharacteristic reticence – I declined this kind offer.

My own requirements were less exotic. The colour combinations available to me were almost without number, but I knew what I wanted: black and grey. The effect should be almost as if I were wearing grey spats over black shoes - something I did, indeed, do in my daring youth. Mr Schweiger knew at once what I wanted, and produced a sample of dove-grey glacé kid leather of exactly the right tone. The style would be unusual, but quite possible: a whole cut galosh (that is, with no side seams), full brogue, Oxford cut, with a hint of chisel to the shape of the toes. The soles would be shaped in the manner of a violin, for greater lightness. As is my usual custom, I would have two rows of nails at the toe of each sole, to inhibit wear, and quarter metal heels, to make a pleasing 'click' on the pavement. The leather for the soles would be oak-bark tanned, from Barkers tannery in Devon, and the leather for the uppers would be from the Freudenberg tannery in Weinheim in Germany. Mr Schweiger wondered whether I might like the 'punching' on the toes to incorporate a monogram of my initials, but – displaying an uncharacteristic reticence – I declined this kind offer.

Prices for bespoke shoes with welted soles at James Taylor and Son begin at £1,450, plus V.A.T. My shoes would be £1,700, plus V.A.T. (£1,997.50, including V.A.T.) The arrangement is that 75% is paid at the time of the order, with the balance on collection. (Alternatively, a discount of £35 is offered for full payment at the time of order.)

Mr Schweiger measured and drew my feet. This process, for which I stood on the measuring board, was detailed and thorough and took fully ten minutes. I asked who else would be involved in the making of my shoes. I had not thought there would be so many... Lee would shape the lasts from hornbeam (a type of beechwood), ensuring that the toe shapes, heel pitches and measurements were correct. Fiona would cut the pattern. Mary would cut the uppers (a process called 'clicking') and the linings. Bambos would sew the uppers, having 'skived' all the joins and punched the holes for the broguing. Samantha would fit up the necessary materials – the insoles, the stiffeners, the toe puffs and so on, and pass them on to Dave, who would pull the uppers over the lasts and prepare the shoes for fitting. After the fitting, Dave would also sew in the welts, sew the soles, bevel the waists and build the heels. Finally, Kevin would finish the shoes, by pulling out the lasts, fitting the leather socks and laces and polishing. (These proceedings are illustrated in the black and white photographs.) These skilled craftsmen – and women – are on the premises, and my picture shows one of their work rooms.

The wooden lasts of customers – about 4,000 of them, all carefully named and numbered - are also on the premises (see picture), awaiting use for repeat orders.

Three months passed. Then the message came that the shoes had reached the fitting stage. I hurried to Marylebone. As soon as Mr Schweiger took them from the box, I saw that the style had been a triumphant success. Although clearly far from finished, the cut and the colour combination already marked out these shoes as special. I wondered what sort of laces should be used. Black? Grey? Flat? Round? I eventually decided upon round black – waxed, for a touch of sparkle. I walked around the shop in the unfinished shoes: the fit and the comfort were perfect.

Three months passed. Then the message came that the shoes had reached the fitting stage. I hurried to Marylebone. As soon as Mr Schweiger took them from the box, I saw that the style had been a triumphant success. Although clearly far from finished, the cut and the colour combination already marked out these shoes as special. I wondered what sort of laces should be used. Black? Grey? Flat? Round? I eventually decided upon round black – waxed, for a touch of sparkle. I walked around the shop in the unfinished shoes: the fit and the comfort were perfect.

Another month and the finished shoes were mine. Look at the pictures carefully. I do not know whether these shoes are unique, but I do know that they achieve a happy paradox, being at the same time both discreet and eye-catching. They are beautifully made, supremely comfortable and – already – have been much admired. The real delight of bespoke shoes has been given to me by James Taylor & Son: I have exactly what I want.

You must be logged in to post a comment.